Giant Sequoia Slab

Arizona State Museum Exhibit

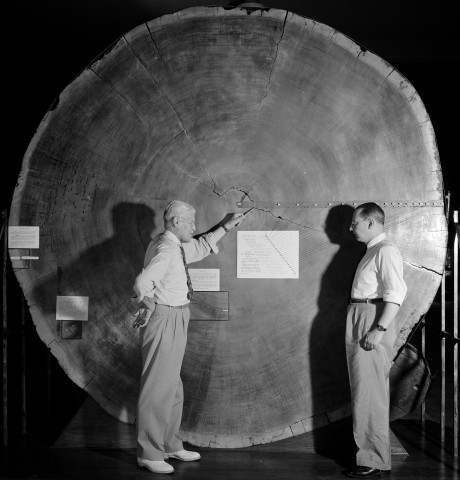

A.E. Douglass demonstrating the original slab display to a visitor: select to see a much larger version of the image (Arizona State Museum).

For many years one of the most memorable attractions at the Arizona State Museum was a large cross-section of a giant sequoia, prepared so that the rings were visible, and marked with the dates of various historical events. A.E. Douglass, the pioneer of tree-ring dating, had played a large part in obtaining this slab for the museum, and there are are several photographs showing him expostulating in front of it. In the image shown here, Douglass (on the left) is pointing to rings formed early in the life of the tree, in the third century CE. The list of historical events is below his hand, with each date literally tied to the corresponding tree ring by pins and a length of string. Immediately in front of him another label identifies an event which was significant for the tree itself: a forest fire that injured it, leaving a scar visible in the pattern of rings, but which did not kill it. The details of the explanations in later exhibits changed slightly, but they continued to convey the same kinds of interpretation.

Disassembly at the Museum

When the Arizona State Museum moved to its present building (the former university library), the giant sequoia slab was left behind in an area that had become used only for storage and offices, not public display. However the Laboratory of Tree-Ring Research has a public exhibit area in its new home (the Bryant Bannister Tree-Ring Building), and this provided an ideal space to restore the slab to public view. Removing the slab from the old museum building was not easy, and required the services of a team of professional riggers. Although there was no need to damage the slab by cutting it into smaller pieces, cracks from a previous move already divided it into several sections, and an iron band around the circumference of the slab was keeping these together. In preparation for the move, the riggers removed the band and gently lifted these sections apart, so they could be carried safely and pose less of a problem fitting through the doors and other constrictions. In the images of the disassembly below, notice how the original metal support is identical to the one visible in the photograph of Douglass in front of the slab above.

Removing the topmost part of the slab (Chris Baisan).

Freeing the main upper piece from the rest of the slab (Chris Baisan).

The main upper piece suspended to the side of the rest of the slab (Chris Baisan).

Lowering the main upper piece to its support (Chris Baisan).

The upper piece safe on its temporary support (Chris Baisan).

Carrying Across Campus

Moving day came weeks after the initial preparations. The riggers rolled the pieces out of the old museum building onto a specially constructed platform at the top of the main entrance steps, from which a large crane could lift them onto a flatbed truck parked outside. Several of the press reports on this operation mentioned that the foreman for the project, Albert Kinder IV, had a father and a grandfather who had both moved the same giant sequoia slab at various times in its history, including the initial move into the museum building. The truck did not have to travel far to reach the Bryant Bannister Tree-Ring Building, but this was still a construction site and the design of the building prevented a crane from placing the pieces, so a fork lift was needed to move them close to the entrance. No doors were yet installed, but the largest piece passed through the opening with very little room to spare. Within, the exhibit area where the pieces were to be reassembled was higher than the entrance lobby, so they could not be rolled directly into place.

Moving pieces from the museum step platform to the flatbed truck (Chris Baisan).

Arriving at the Bryant Bannister Tree-Ring Building; a curved wall partially covered with translucent panels encloses the exhibit area (Chris Baisan).

A forklift moving to the building entrance by a circuitous route (Chris Baisan).

Reassembly at the Tree-Ring Building

Although all the pieces were now moved to the new location, much work remained to be done. The largest piece needed to sit in its new mount, then the three-dimensional jigsaw puzzle of other pieces had to come together on top of it, fitting together without open cracks, and re-forming a single smooth surface on both sides of the slab without any steps. Finally a replacement metal band had to bind all the pieces together. Although the largest piece rolled through the entrance a little after noon, daylight was starting to fade before the reassembly work was nearly finished.

The largest section, transferred to the new mount (Ed Wright).

Lowering the largest top piece into place (Ed Wright).

Fitting a smaller top piece (Ed Wright).

Chris Baisan of the Tree-Ring Lab tightens a bolt (Ed Wright).